Nearly three thousand guests visited the exhibition Listin í smiðju Héðins, held on October 1, 2022. The exhibition was open for this one day only, from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., in the company’s machine halls at Gjáhella. The event was a joint project between the National Gallery of Iceland and Héðinn, marking the company’s centennial. On display were works from a remarkable gift by the family of Markús Ívarsson, who, together with Bjarni Þorsteinsson, founded Héðinn in 1922.

Markús Ívarsson was born in 1884. He was a trained blacksmith and a passionate collector of works by artists of his time. In this way, he consciously supported various artists who lived under difficult conditions, who later in life became a huge suggess.

A Growing Gift

Markús passed away in 1943, only 59 years old. He left behind a vast collection of about 200 works, including oil paintings, watercolors, drawings, and sculptures. In 1951, Markús’s widow, Kristín Andrésdóttir, and their daughters donated 56 works from this large collection to the National Gallery of Iceland.

The donation was announced on August 27, the same day the National Gallery of Iceland was formally opened in its new premises on Suðurgata, on the top floor of the building that now houses the National Museum on all floors.

And the family of Markús did not stop there. In 1966, they additionally presented the collection with a work by Jóhannes S. Kjarval, Sjá roðann á hnjúkunum háu, from 1930. In 1997, on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the Héðinn Machine Workshop, they donated to the museum Dettifoss by Sveinn Þórarinsson. And in 2007, the family added to the holdings of the National Gallery of Iceland a portrait of Markús Ívarsson by Jón Stefánsson, painted in 1934. The painting depicts Markús in a blue overall, with a thoughtful expression, holding a hammer and chisel.

Masterpieces

Markús began a deliberate collection effort at a crucial moment, when new generations of artists were emerging in the 1930s but struggling during the Depression years, and his support often proved decisive.

In general, Markús’s collection represents a very fine selection of Icelandic art from the first half of the last century. Among the works are key pieces by several of the nation’s most important artists.

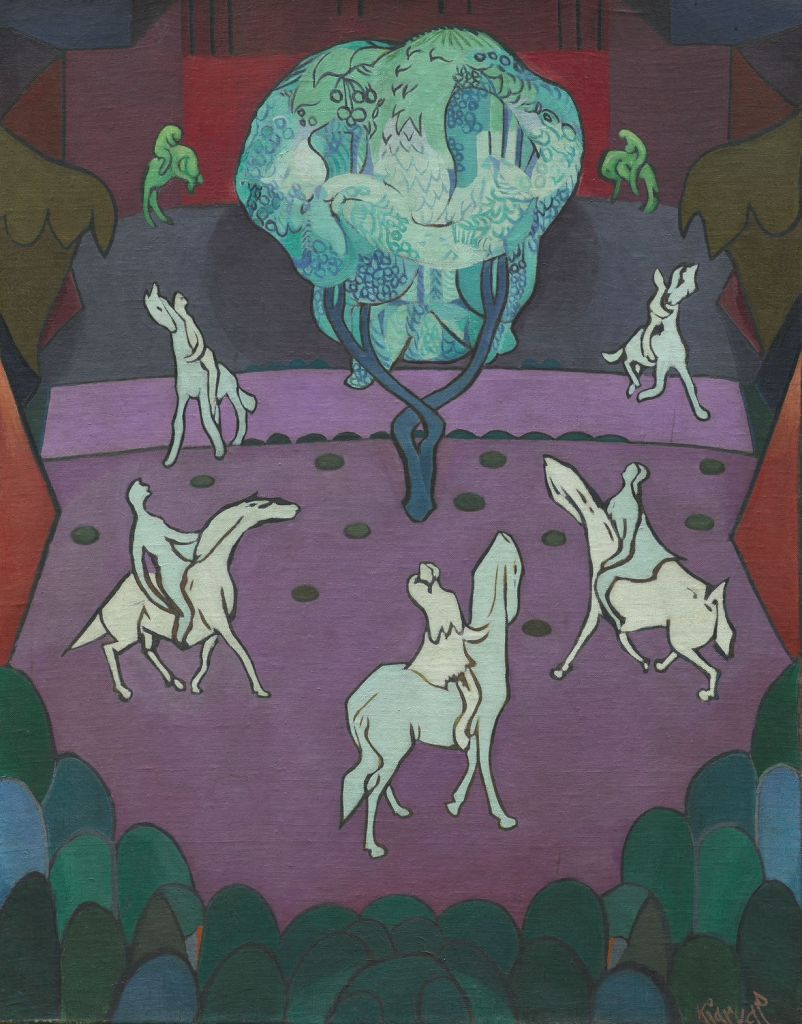

Icelandic Artists at the Tree of Understanding, from 1919, by Jóhannes Kjarval (1885–1972).

The themes and subject matter are diverse in the exhibition Listin in Héðinn’s Workshop. The paintings include portraits, beautiful depictions of rural life, dramatic images of wilderness landscapes, as well as scenes of harbor and town life. Display cases feature a selection of drawings and watercolors by Muggur, Greta Björnsson, Höskuldur Björnsson, and others. Also on view is a small gem, the watercolor Baula by Svavar Guðnason, from 1934.

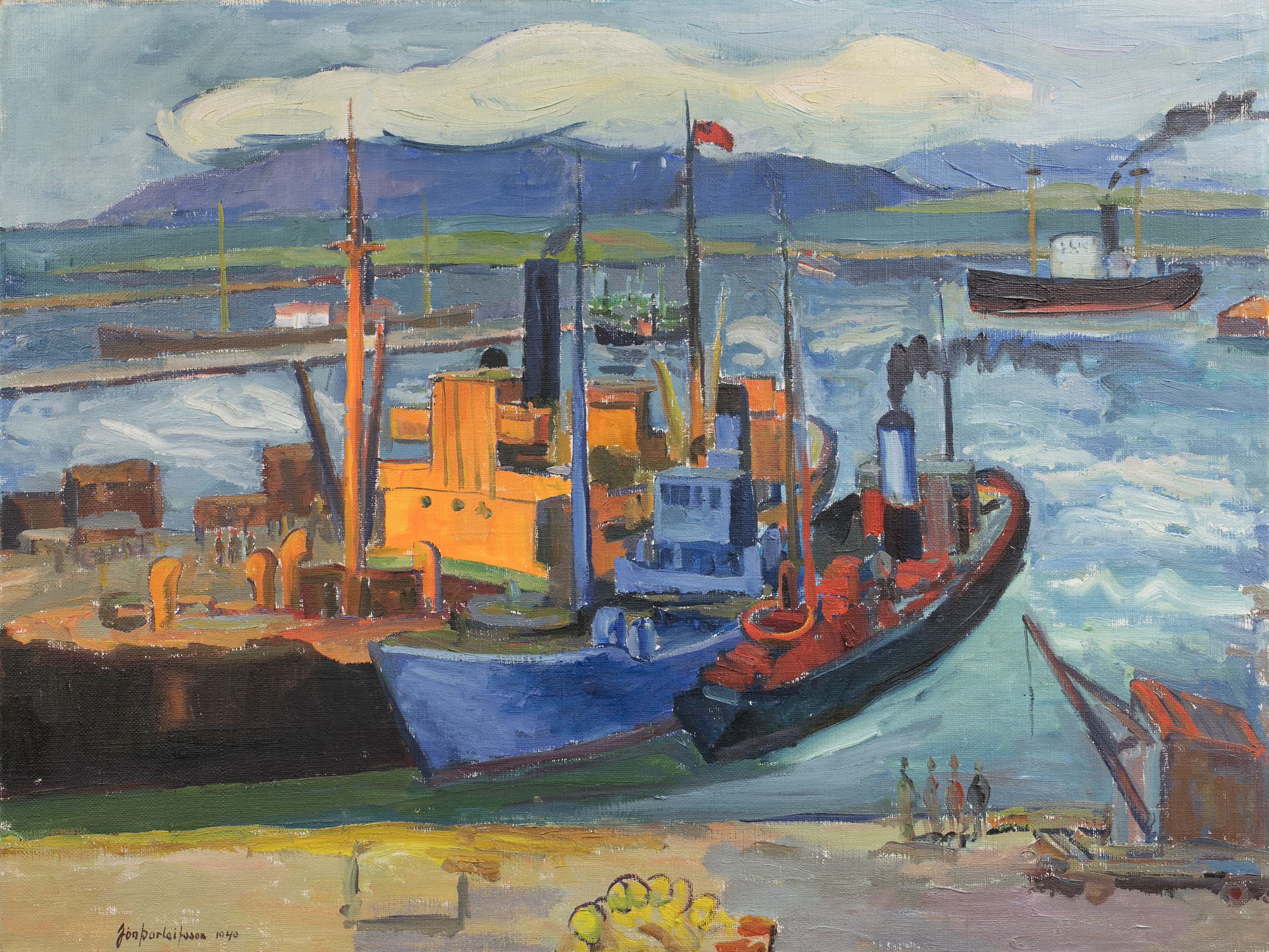

Thanks to the donation from Markús’s family, the National Gallery received important works from a turbulent period in the mid-20th century. Among them is Úr slippnum by Snorri Arinbjarnar, from 1936, which vividly captures the oppressive atmosphere of the Depression years while also reflecting the new themes and subjects of young artists who were at that time returning home after studying abroad. This clearly demonstrates how a private collection such as this can influence the shaping of Icelandic art history.

The story of how Jón’s portrait of Markús came to Iceland.

The family of Markús Ívarsson had long known of the portrait that Jón Stefánsson painted of his friend in 1934. The work was in Copenhagen with Jón’s widow, Mrs. Erna Stefánsson. Sveinn at Héðinn, Markús’s son-in-law, often visited Mrs. Erna to try to persuade her to sell him the painting, but without success. (In fact, it was believed that Markús had already paid for the painting long before, but Jón took that information with him to the grave.)

Markús Ívarsson, from 1934, by Jón Stefánsson (1881-1962).

It happened once, shortly after 1960, that Ingvar Vilhjálmsson of Ísbjörninn was in Copenhagen with his son Jón when he paid a visit to Jón Stefánsson’s widow to buy paintings. At that time, prominent men had the custom of purchasing works by the great names in Icelandic art to present to one another as gifts. Ingvar leafed through Jón’s paintings, saw the portrait of Markús, and persuaded Mrs. Erna to sell it to him for 18,000 Danish kroner. Jón, Ingvar’s son, then carried the portrait with him on the Gullfoss vessel and kept it in his cabin during the voyage to Iceland. When they arrived in Iceland, Ingvar handed the painting to his neighbor Sveinn at Héðinn, who paid the agreed price. From then on, the painting was considered the property of Markús’s descendants until it was donated to the National Gallery of Iceland in 2007.

In the book Íselnsk portrett á tuttugustu öld (Icelandic Portraits in the Twentieth Century), Aðalsteinn Ingólfsson unhesitatingly places the portrait among the masterpieces of Icelandic art. He is convinced that Jón would never have been able to get away with painting an Icelandic entrepreneur—even a former blacksmith—in his old work clothes, hammer and chisel in hand, had that entrepreneur not held an almost boundless respect for the artist’s calling. ‘The portrait of Markús Ívarsson is a unique tribute to an almost extinct type: the youth-movement hero, with calloused hands and a mind filled with patriotism and poetry.’ (Aðalsteinn Ingólfsson, Íslensk portrett á tuttugustu öld, Hafnarborg 1996 p. 28.).)”

Send us a message

Fill out the Form