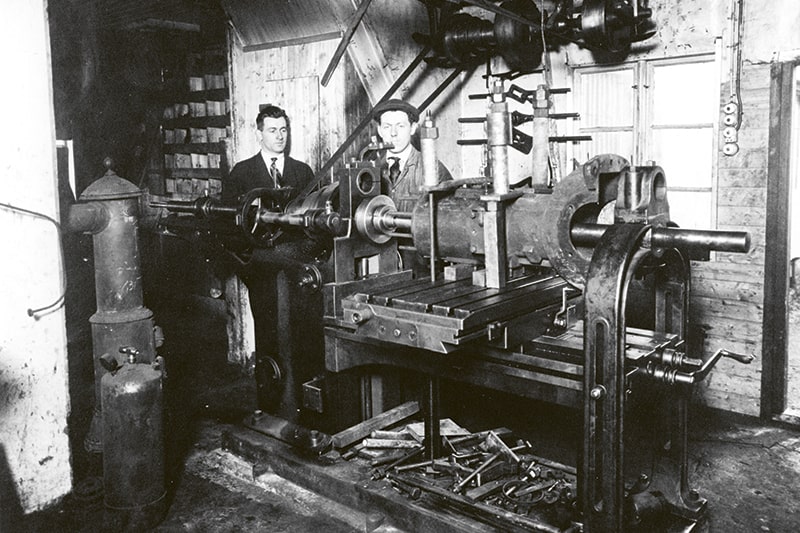

Apprentice No. 1, Jafet Hjartarson, was the first to begin training with the men of Héðinn in 1923. Here he is, on the right, at work under the watchful eye of master Bjarni Þorsteinsson, one of Héðinn’s founders. The two lathes were at first powered by an "ALFA"-type oil engine, until electric motors were later installed. Photo: Author unknown / Héðinn.

The Subsidiary Járnsteypan in Reykjavík

In 1933 it was decided to establish Stálsmiðjan, a partnership between the machine workshops Héðinn and Hamar. Hamar contributed the company Járnsteypan to the venture, which went on to play a major role in Héðinn’s operations, as the foundry became the foundation of Héðinn’s production during and after the mid-20th century. Virtually all of the company’s manufactured products originated, to a greater or lesser extent, in Járnsteypan.

Many of the leading pillars of society at the beginning of the last century took part in establishing companies in the iron industry for a new era. It can thus be said that the cream of Iceland’s emerging middle class took part in founding the Járnsteypa Reykjavíkur in 1905. The initiative, however, came from the brothers Gísli and Sigurgeir Finnsson, blacksmiths who were both imaginative pioneers in various fields of new industries. The foundry was carefully prepared, and its provisional board consisted of Gísli Finnsson, blacksmith; N.B. Nielsen, commercial agent; and Jón Þorláksson, engineer and later Prime Minister.

Magnús Benjamínsson, watchmaker, and Jón Pálsson, organist, served on the alternate board along with Jón Brynjólfsson, shoemaker and leather dealer. Fundraising for share capital went well, and optimism prevailed about the future. At the general meeting, Gísli Finnsson was elected chairman of the board, with Jón Brynjólfsson and Jón Pálsson as board members, and N.B. Nielsen as alternate. The first managing director of Járnsmiðja Reykjavíkur foundry was Jes Zimsen. Among other shareholders were Hjalti Jónsson of Eldey, August Flygering, merchant and the directors of both of the country’s banks, Tryggvi Gunnarsson of Landsbanki and Sighvatur Bjarnason of Íslandsbanki.

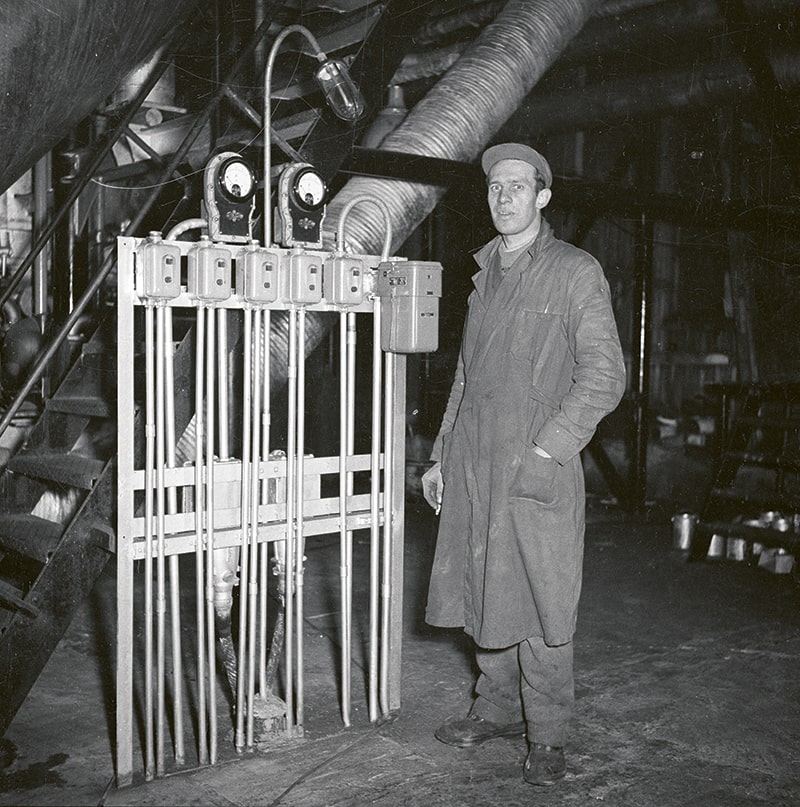

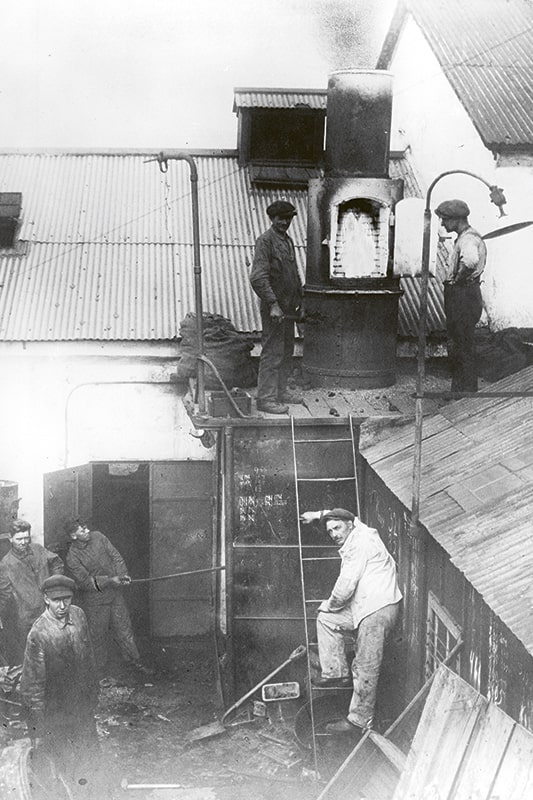

Metalworking — From the earliest days of the Iron Foundry. For a long time, the metal was melted in a cupola furnace fired with coke. The coke, along with the pig iron, was hoisted to the top of the furnace by hand, a task that was very laborious.

Later, production was modernized with electric smelting. Photographs: Author unknown / Héðinn.

Events in World Politics

The company’s first mold maker was a Danish man, Knud Jensen, but then Jónas Jónasson of Hlíðarhús took over that role and made all the molds during his lifetime. After his death in 1915, molds were made in various places, mostly by Árni Jónsson, a carpenter at Nýlendugata 21, until the year 1925.(5)

Sigurgeir Finnsson was the foreman during the first semesters. But in 1908 the iron foundry, Járnsteypa Reykjavíkur brought in an excellent craftsman from Denmark, Valdimar Poulsen, to run the workshop. He did not stay long, however, and established another workshop. Járnsteypa Reykjavíkur nevertheless continued its operations – and in 1910 Árni Jónsson, who had been an apprentice during the foundry’s first year of operation, took over as foreman. But it was not long before changes followed in the wake of world political events.

As the First World War went on, the operating difficulties of the iron foundry Járnsteypa Reykjavíkur increased with the rising price of coal used for smelting. Eventually, it was decided to sell the business.

At the end of the First World War, in 1918, Járnsteypa Reykjavíkur became part of a company group that was established under the name of the machine workshop Hamar.

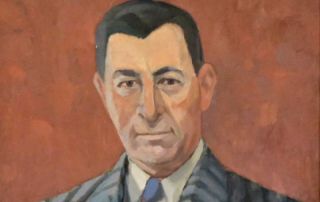

Markús Ívarsson and Bjarni Þorsteinsson worked together at Hamar before they founded Héðinn in 1922, and from the beginning they had various forms of cooperation with their former workplace, even though they also competed for projects. Engineer Benedikt Gröndal became managing director of Hamar in 1932, and the ties between the companies grew even closer.

It can be said that the activities of iron foundry grew during the interwar years, both because Icelanders increasingly felt capable of doing more in this field, and also because it was regarded as a matter of national independence that as much as possible should be produced within the country. Nevertheless, the industry continued to benefit from foreign labor and ideas. For example, around the mid-1930s, a Danish mold maker named Svendsen was brought in to work with Járnsteypa Reykjavíkur.

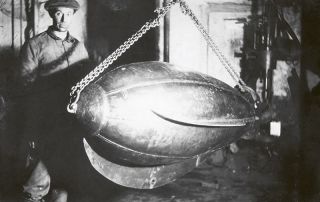

Not every venture turns out profitably. The Dane Emil Andersen came in 1926 to teach Héðinn’s employees how to use the company’s first electric welding machine. In the picture is a buoyancy tank that he and other Héðinn workers had just finished welding together. The tank was built for the trawler Gylfi for experimental fishing with a pelagic trawl. Unfortunately, the trial failed, as the tank collapsed under pressure on its very first descent into the depths. Photo: Author unknown / Héðinn.

The Cooperation of Hamar and Héðinn

n 1933 it was decided to establish the steelwork: Stálsmiðjan – a joint partnership of Héðinn and Hamar. It operated in a factory building on Brunnstígur. Finally, in 1940, an agreement was made between Héðinn and Hamar for the joint operation of an iron foundry, and Tómas Vigfússon was commissioned to oversee the construction of new facilities for that activity. The reason was that demand for iron casting had been steadily increasing, and the old premises had long outgrown the operations.

That building was completed in 1941, when the joint company Stálsmiðjan finished constructing a factory for Járnsmiðja Reykjavíkur, designed to accommodate all types of metal casting. The building measured 12 by 50 meters, and it was estimated that between 30 and 40 people could work there. It was erected on an old lot formerly belonging to the Alliance fishing company on Hringbraut, where drying sheds had once stood, though the planned extension of Hringbraut was to pass through this area of Vesturbær. With this new construction, Héðinn formally became a half-owner of Járnsmiðja Reykjavíkur.

In the first period after the war, a protectionist policy prevailed in favor of Icelandic industry, but after 1960 there was increasing pressure to abolish tariffs and import duties on industrial goods in the lead-up to Iceland’s accession to the EFTA free trade association. Icelandic manufactured products had to give way to imports and disappeared from production, such as stoves and washing machines. Instead, Járnsmiðja Reykjavíkur took part in Héðinn’s services to the fishing fleet, fish processing, power plants, and heavy industry, which increasingly required its products and services.

Annealed for three days. These pictures are from the war years and were taken at the headquarters on Seljavegur. They show the machining of the main engine of the trawler Hallveig Fróðadóttir. The engine block was annealed: placed on a bed of coal, covered with turf, lit underneath, and left to glow for three days.

Járnsteypa Reykjavíkur becomes part of Héðinn

According to historian Sumarliði R. Ísleifsson, in his summary history of Járnsteypan, the average annual production between 1962 and 1989 was about 153 tons of iron, 5.2 tons of copper, and about one ton of aluminum. However, the workforce varied over time: around seventeen to twenty people worked there around 1970, but only six to eight by 1990. Various technological innovations during this period explained the reduction in staff.

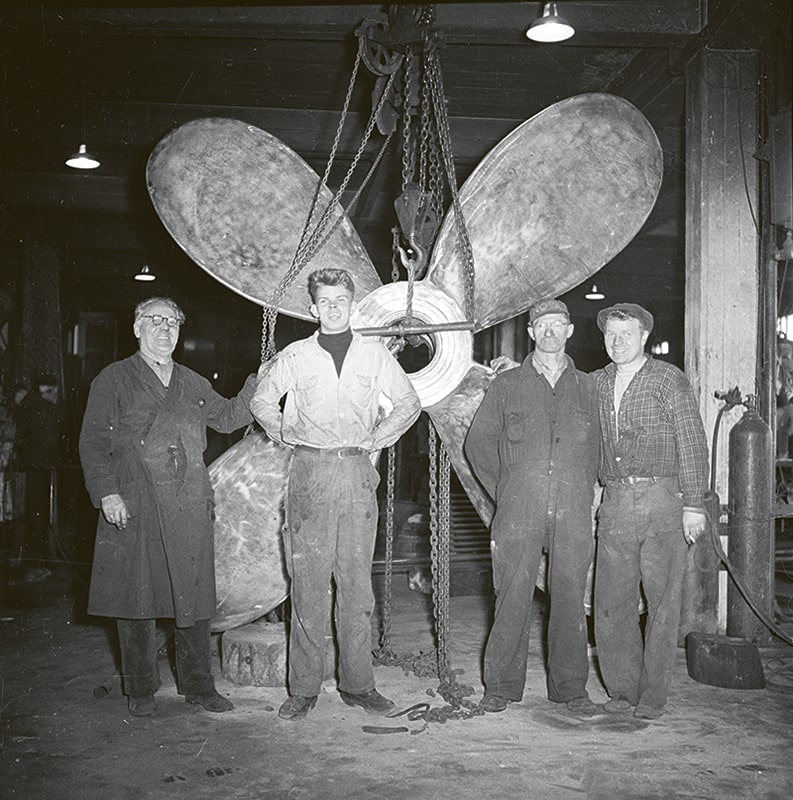

The tasks of Járnsmiðjan varied, differing somewhat from period to period. In the earliest stage, window frames and stoves were cast, but increasingly castings were made in service of the fishing industry: pistons, davits, propellers, and engine parts. Among the more traditional projects were all kinds of frames, benches for street construction (the ‘bus stop bench’), and specially marked manholes – and for the municipalities, various grates, frames, and water traps.

Icelandic artists found both refuge and assistance with the master metal casters of Héðinn and Járnsteypan. In fact, there were virtually no limits to what Járnsteypan was asked to produce. Over time, a remarkable collection of molds was created, perhaps without equal anywhere in the world. It was therefore a great loss in cultural history when, on April 8, 1993, a fire broke out in Járnsteypan – and most of the molds, preserved since 1906, were destroyed.

As mentioned earlier in this account, the machine workshops Héðinn and Hamar jointly owned Stálsmiðjan and thus shared ownership of Járnsteypan in 1941, but in 1985 a division took place. Hamar took over Stálsmiðjan, while Héðinn acquired Hamar’s share in Járnsteypan, and since then the operation has been solely in the hands of Héðinn.

In Garðabær and Hafnarfjörður

After nearly 100 years of operation in Vesturbær, Reykjavík, Járnsmiðjan moved to Stórás in Garðabær and was operated there under the same roof as Héðinn in the following years. And when Héðinn built new premises for its operations at Gjáhella 4 in Hafnarfjörður in 2008, the more than century-old Járnsteypa moved along with it.

Long-lived homebuilt machine. This crane truck was designed and built on top of an American army truck by Héðinn’s workers and was used for every conceivable task in the company’s operations for decades. Above it can be seen a Loftleiðir DC-8 jet coming in to land at Keflavík Airport. The picture was probably taken in October 1971, when the first Loftleiðir DC-8 arrived in Iceland. Photo: Author unknown / Héðinn.

Send us a message

Fill out the Form